I love asparagus. Really love it. I could eat it everyday for the duration of its short season and not get bored. In fact I would probably have it nearly the same way each time, nice and simple with good butter or oil. I might steam it, roast it or chargrill but I’d still dress it simply. I might have it with some cured ham or hard tangy cheese. But in the main I’d let the asparagus do all the talking.

And once the season was over that would be it. No more asparagus for a whole year. Because even more so than other vegetables asparagus loses much of its taste if its transported any distance. Not for me asparagus flown in from Thailand or Peru or Chile, it just doesn’t taste good enough to justify its price or its carbon footprint. The perfect situation for me would be to grow some in the garden but we don’t really have the space to create raised beds and London clay doesn’t make asparagus happy. I might dare to try it in a large tub and see how I get on; even a few home grown spears would be a wonderful thing to have. Until then though I’ll buy at local farm shops and PYO to get the best flavour. And I’ll eat and eat it until the season is done.

The short season usually starts in late April (traditionally St George’s Day) and lasts through to mid June though of course this is dependent on the weather during winter and early spring. Anywhere with sandy soil is good for asparagus growing and each well-known area from Formby in the North West to East Anglia and the Vale of Evesham stake their claims for being the best. Of course the best asparagus is what you can find that has been picked very recently and arrived in your kitchen quickly and landed on your plate ready to eat with minimal fuss.

Asparagus has always been prized and ‘The Neat House Gardens’ relates how the early market gardens surrounding London vied to produce asparagus as early as Candlemas by use of hot-bedding techniques and the liberal application of horse manure sent out from the city with the forced vegetables being sent back for consumption by the rich. Up to at least Mrs Beeton’s time asparagus continued to be forced and available from January. But at some point forced asparagus seems to have disappeared so either it didn’t taste much good or the cost became prohibitive, by the time Jane Grigson is writing about it in the 1970s there is no mention of it.

Times have changed in terms of cooking as well. Modern books suggest it takes about 8-12 minutes to steam whereas in the 1800s Acton, Beeton et al were saying 20-25 minutes of boiling and Grigson says it can take anywhere between 20-40 minutes. Goodness knows how big the spears needing 40 minutes were! Maybe the varieties grown have changed and we certainly seem to prefer our vegetable with lots more crunch than in the past but still 40 minutes seems extreme unless the aim was to make puree. Also common was to serve asparagus on toast to soak up some of the water from the boiling, steaming of course gets rid of this problem. And naturally the Victorians’ had special asparagus tongs for serving, mind you I think they had special cutlery for serving just about everything you can think of.

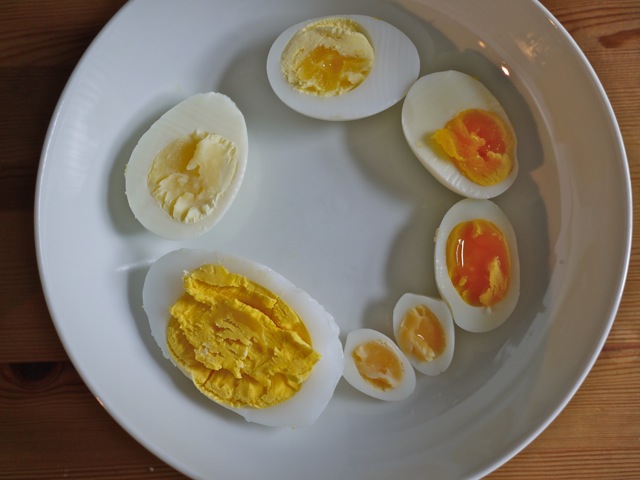

Recipe wise asparagus is often paired with eggs: hollandaise, dipped in boiled eggs, in omelettes, with fried egg in tapas, in tarts and quiches. Salty cheeses and cured meats also make great partners. Then there is the classic soup (which I have to confess I’ve never tried). Oh and of course with salmon or crab or chicken or….well almost endless possibilities. Googling ‘asparagus recipes’ gives 3.3 million hits so there is no shortage of ideas out there. One site I do recommend though is Fiona Beckett’s http://www.matchingfoodandwine.com/ which will help you pick the right wine to enjoy with your treasured asparagus; focus on how you are serving it to help you make a good choice.

Because you can easily find so many ways to serve asparagus I thought I’d offer you something a little different. Flipping through various books I found a recipe from Hannah Glasse in 1747. Here it is (complete with archaic spelling and quirks):

Asparagus forced in French Role

Take three French Roles, take out all the Crumb, by first cutting a Piece of the Top-crust off; but be careful that the Crust fits again the same Place. Fry the Roles brown in fresh Butter, then take a Pint of Cream, the Yolk of six Eggs beat fine, a little Salt and Nutmeg, stir them well together over a slow Fire, till it begins to be thick. Have ready a hundred of small Grass boiled, then save Tops enough to stick the Roles with; the rest cut small and put into the Cream, fill the loaves with them. Before you fry the Roles, make Holes thick in the Top-crust to stick the Grass in; then lay on the Piece of Crust, and stick the Grass in, that it may look as if it was growing. It makes a pretty Side-dish at a second Course.

Inspired by this I did:

Asapargus and Egg Rolls:

Serves 1 for lunch

1 crusty French roll or half a small baguette

8 spears of asparagus

1 large or two small eggs

Mayonnaise (fresh or your favourite shop bought)

Cut the top off the roll, remove some of the crumb or else you will face the dangers of squirting egg mayonnaise everywhere. Hard boil the egg(s) and make into a light egg mayonnaise with as little mayonnaise as will just bind the eggs. Part steam or blanch the asparagus and then finish on a chargrill. Slather the egg mayonnaise on both sides of the bread. Put the asparagus on the bottom part of the roll. Put the top of the roll back on. Serve with salad. Watch out for escaping egg mayonnaise.

This article was first published in Francoise Murat & Associates newsletter in May 2010.